I often describe the dedication involved with a career in research as well as how scientists can spend their entire careers studying a very specific aspect of a disease process. I enjoyed reading this article about Dr. Kati Kariko, a Hungarian-born scientist, whose research laid the foundation for the future of the mRNA vaccines which today protect us against COVID-19.

Category: Uncategorized

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19

Preliminary data from California on COVID-19 cases and deaths through May 20, 2020 suggest racial/ethnic disparities in adults diagnosed and dying from the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV2. While there were substantial amounts of missing data (30% of cases and 2% of deaths were missing information on race/ethnicity) and data are dependent on testing to identify cases, two patterns have emerged. First, adults of Latino and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander race/ethnicity are disproportionately more likely to be infected with SARS-CoV2 relative to the proportion of the California population that they make up. Adults of African-American/Black race/ethnicity made up a greater proportion of deaths from COVID-19 relative to their proportion of the California population. The demographic data do not tell us why these patterns may exist but some hypotheses have been put forth. Cases, which indicate infection with COVID-19, may be associated with socioeconomic factors, such as, employment in essential occupations, being less able to work from home or less able or compliant with social distancing. Deaths, which indicate more severe disease once infected, may be reflective of less access to health services, more prevalent comorbidities, or vitamin D deficiency (vitamin D is essential to immune function). More research is needed to examine these potential racial/ethnic disparities.

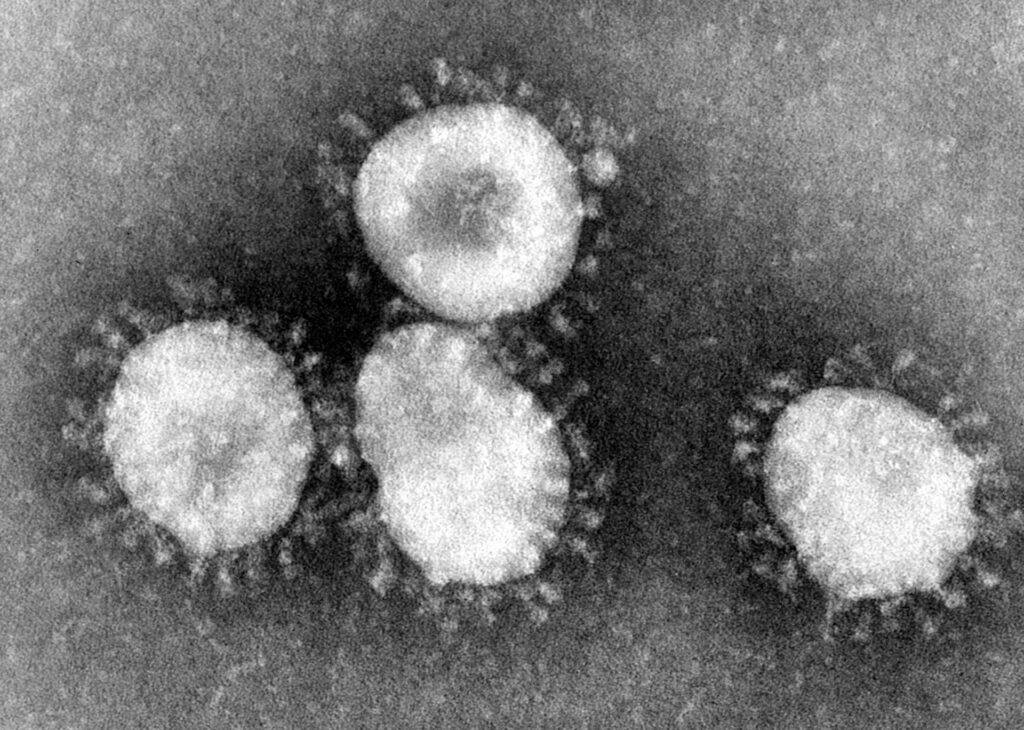

The earliest images of coronaviruses

Ever wonder how scientists were first able to get a glimpse at coronaviruses? In 1964, a female virologist named June Almeida with an acumen for viral imaging using the electron microscope visualized coronaviruses for the first time. A recent National Geographic magazine article describes her microscopy techniques which allowed researchers at the time to discern one virus from another as well as to identify viruses that were previously unseen. And as it turns out, researchers today are still using her techniques to accurately identify viruses.

Pandemic EpiSpeak

Students who have taken one of my classes in epidemiology at CGU will probably remember me saying that learning epidemiology is, in many ways, comparable to learning a new language. Like many other fields, in epidemiology, we use specific words to indicate specific things. Hopefully my students are having fond memories right about now of the terminology we learned in class, for example, to describe disease occurrence in populations.

Our “EpiSpeak” also includes terms used in efforts control epidemics, as we are currently with the COVID-19 pandemic. I’ve heard some mixing of terms circulating such as referring to our stay-at-home order as “quarantining”.

Here is some clarity on three key terms: isolation, quarantine and physical distancing (also called social distancing) citing the World Health Organization.

“Isolation means separating people who are ill with symptoms of COVID-19 and may be infectious to prevent the spread of the disease.”

“Quarantine means restricting activities or separating people who are not ill themselves but may have been exposed to COVID-19.” By anticipating who might become sick, the goal is to prevent spread of the disease at the time when people just develop symptoms.

“Physical distancing means being physically apart. WHO recommends keeping at least 1-metre (3 feet) distance from others. This is a general measure that everyone should take even if they are well with no known exposure to COVID-19.” A goal of physical distancing is to slow the spread of disease by reducing the number of interactions we have with each other.

Be a steward of epi and apply these terms precisely! A benefit of this, I hope, is that we can reduce some of the confusion that is circulating and help to answer the question, “what can I do in the face of this pandemic”?

Inhale: Spring!

With all the scents of spring in the air, the least sensible thing I’ve done is to hesitate to breathe deeply the aromas fearing what else I’d take to my lungs!

Public Health and the Coronavirus: We should be pointing fingers at ourselves

When Congress reserved hot seats last week for two of our nation’s top health officials regarding the coronavirus epidemic in the US, it came as no bombshell revelation to my fellow public health colleagues to hear our system described as a “failure” during the testimony of the NIH’s Dr. Anthony Fauci. In truth, our situation in public health is akin to the same bad joke that keeps on being told: we are chronically underfunded to do the work we do to keep the public – Americans – healthy and safe. This unfortunate circumstance is well-known across public health circles; we talk about it as part of our schooling, discuss it at conferences, and cope with it in our workplaces. We in public health have become accustomed to doing more with less and being regarded as the step-sibling to our brothers and sisters in the medical profession. In some ways, we public health professionals can be understanding. Afterall, we recognize that it is difficult to perceive the fruits of our labors: prevention efforts keep people from getting sick (how really does one quantify the absence of disease?). We get that it is much easier to grasp what our medical counterparts do when a disease is treated and cured. Here my public health training prescribes that I point out how preventing disease is generally less costly than treating disease. Prevention approaches – be they vaccinations for infectious diseases, educational programs or anti-smoking policies – are some of the most effective interventions we have available, and they save lives. Prevention also means readiness; insufficient funding over time has had impacted our ability to anticipate, prepare and respond quickly and nimbly to threats such as natural disasters or novel viruses, such as is apparent today with COVID-19. The reality is that we need public health more than ever: we will face new challenges with continued population growth, global travel and migration, and changing habitats due to climate change. To succeed, our priorities need to shift as a nation. We need to support funding for public health. We need to vote for elected officials who value public health and advocate for public health with those in office. Public health is, at its core, just that – the health of the public. We all play a role in our public health, highlighted by the coronavirus epidemic. Otherwise, we can’t fairly criticize our public health professionals and need to save the finger-pointing for ourselves.

Staying abreast of the coronavirus situation

The novel coronavirus is a rapidly changing situation for public health. I personally have found that some of the information I read in the morning newspaper may already be outdated by the time I am driving into work and listening to news coverage on the radio. This, coupled with the sheer number of sources of media can inevitably be confusing and difficult to follow. It is good to stay updated on the situation in order to be informed of recommendations by public health professionals. Pick a few sources that are trustworthy and check them regularly.

For example:

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health has a webpage dedicated to the novel coronavirus: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/media/Coronavirus/ as does the Riverside University Health System: https://www.rivcoph.org/coronavirus and the San Bernardino Department of Public Health http://wp.sbcounty.gov/dph/coronavirus/

One of our local public radio stations, KPCC 89.3 FM, is regularly broadcasting live updates from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Or you can follow the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) @CDCgov or the World Health Organization (WHO) @WHO on Twitter which both offer daily briefings on the coronavirus.

Why the public health response to the novel coronavirus may be shifting

The term “community transmission” is being used to describe what public health officials believe is the likely way a Northern California resident became infected with the COVID-19 virus this month. This description refers to the fact that the infected woman had not traveled internationally, had contact with anyone who had, or with anyone who was known to be infected with the virus. As such, it is possible that she was exposed to the virus through someone else who didn’t know they were infected. A problem with emerging infectious diseases such as that caused by the novel coronavirus, is just that – they are not known to us and the unknown inevitably can cause some to fear the worst. What will help to shed light on the situation is more information and good quality information. International data on the COVID-19 virus thus far seems to suggest that approximately 80% of people who become infected do not develop severe illness. We still have more to learn about COVID-19 and public health officials are planning to expand testing for the virus. What we do know is that COVID-19 causes respiratory illness; as with other respiratory viruses, the best prevention still relies on simple steps like covering coughs and sneezes, washing hands, staying home when sick and avoiding contact with others who are. So, yes, we should be taking this new virus seriously and taking precautions, but we also should direct our fear energy to preparedness efforts.

Fear the coronavirus… or the flu?

The media plays an important role in public health: communicating information, educating the public, serving as an avenue for discourse on a given topic. At worst, reporting by the media and particularly social media may fuel xenophobia as described in this February 3 LA Times article. While we don’t know yet the scale and magnitude of the novel coronavirus globally and in the United States, it is likely that the fear of the unknown is contributing to our perception that the risk is greater than it actually is in the US. This January 31 LA Times article nicely points out what we do know, which is that our annual influenza epidemics a.k.a. “flu seasons” are more cause for concern among Americans. The flu may be “old news”, requiring effort by public health officials to remind people every year to get the flu shot, cover coughs and sneezes, wash hands and stay home when sick.

A new virus?

A newly identified coronavirus, which was first detected in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China in late 2019, has begun to sicken people in China and other countries including the United States. Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses named for the crown-like shape of spikes on their surface. Seven coronaviruses including the newly identified virus, SARS, and MERS, are known to infect humans, primarily causing respiratory illnesses. Other coronaviruses circulate among animals, and rarely do animal coronaviruses evolve to be able to infect people. In the case of the newly identified coronavirus in China, health authorities suspect a large seafood and animal market was the origin of the outbreak, which suggests that at least initially there was animal-to-person transmission. However, a growing number of patients reportedly have not had exposure to animal markets, indicating person-to-person transmission. At this time, the CDC reports that it is unknown how easily or sustainably this virus is spreading between people.

Why worry? Outbreaks of new virus infections among human populations are always of public health concern. At the outset of an outbreak, much is unknown and remains to be discovered. How many people will be infected? How quickly will the outbreak spread? How sick will infected people become? Will there be deaths associated with the infection? Many answers to these questions depend on characteristics of the virus, and many will depend on and the medical or public health interventions available to control the impact of the virus (for example, vaccine or treatment medications).

As of January 24, the CDC and other international health authorities are continuing to monitor the situation and updates are likely as more information is collected.